The Split in the AFL-CIO and the Organization of the Unorganized

Submitted on Sun, 07/31/2005 - 2:11am

From the WORLD SOCIALIST WEB SITE:

Disclaimer - The IWW is not affiliated with the World Socialist Web Site or the International Committee of the Fourth International. This article is published for informational purposes. It's inclusion here does not imply endorsement of the above organizations nor do they necessarily endorse or support the IWW.

By Barry Grey - 28 July 2005.

By Barry Grey - 28 July 2005.

In the current split within the AFL-CIO union federation, both sides are raising as an urgent priority the organization of non-union workers—now the overwhelming majority of the American workforce.

The Change to Win Coalition, headed by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and the Teamsters, both of which announced their disaffiliation from the AFL-CIO on Monday, points to the net loss of 800,000 union members since President John Sweeney was elected ten years ago as justification for its move to break away from the 50-year-old union federation.

There can be no serious argument that the continued decline in union membership under Sweeney’s watch—to less than 8 percent of workers in the private sector—is an indictment of the policies and leadership of the AFL-CIO. But Sweeney, for his part, is also raising the need to organize as a top priority and pledging to dramatically increase the AFL-CIO budget for unionizing drives, and to restructure the federation to better coordinate such activities. His line of attack is that the defection of the 1.8-million-member SEIU and the 1.4-million-member Teamsters, likely to be followed by the split-off of other Change to Win unions, undermines the efforts of the labor movement to win new recruits.

Both camps raise the mantra “organize the unorganized” as the critical issue in the survival of the labor movement. That workers need to unite and organize to withstand the daily assaults of the corporations on their jobs, working conditions and living standards is something that is deeply felt in the working class. And decades of betrayals and collusion with management on the part of the unions have left not only non-union workers, but also those within unionized industries, in an immensely weakened position to resist the attacks of the employers and defend their interests.

What, then, is to be made of the newfound enthusiasm of the union officialdom—on both sides of the split—for organizing?

In a word: it lacks any credibility. In the first place, the pledges to turn the tide and begin a new era of union growth and power are not connected, in either camp, with any serious analysis of the historical, social or political roots of the collapse in union membership—a process that has been underway ever since the AFL and CIO merged in 1955. Nor is there any coherent perspective advanced for how this decline is to be reversed.

There is no questioning of the defense of the profit system that has been the cornerstone of the outlook of the AFL-CIO since its formation. Neither side raises the great historical question of the subordination of the American labor movement to the two-party system—with all of its disastrous consequences for the working class. While both sides give lip service to international solidarity and the need to coordinate with workers in other countries against global corporations, they support the imperialist foreign policy of the US ruling elite, including the war in Iraq.

Andrew Stern, the president of the SEIU, points to his union’s success in increasing its membership—by some 900,000 over the past nine years—to bolster his claim to be the leader of a resurgent labor movement. But Stern has benefited from the enormous growth in the low-wage service sector of the economy, in no small part at the expense of manufacturing. Most of his union’s gains have come from reaching deals with companies and local and state governments permitting the SEIU to enroll janitors, security guards and home health care providers at sub-standard wages and limited benefits, in return for helping to stabilize the work force and boost the corporate bottom line.

One would have to be naïve in the extreme to believe that either he, the Teamsters’ James P. Hoffa, or Sweeney and his cohorts have any serious intention of mounting the type of struggle it would take to organize any significant section of the nearly 90 percent of the workforce that is non-union.

If, however, we engage for a moment in a willing suspension of disbelief and take these union officials at their word, then we must consider what it would really take to bring tens of millions of workers into the unions.

The only precedent in US history is the birth of the CIO unions in basic industry in the 1930s. But these unions—in auto, steel, rubber, electrical, telephone—arose out of massive working class struggles that assumed semi-insurrectional dimensions. There was, in the depths of the Depression, a burning desire on the part of the broad mass of unorganized and unskilled workers to establish unions in order to secure a living wage and a modicum of job security, not to mention basic human dignity. This social force erupted first in a series of mass strikes in 1934—in San Francisco, Toledo and Minneapolis—that were led by socialists and left-wing radicals.

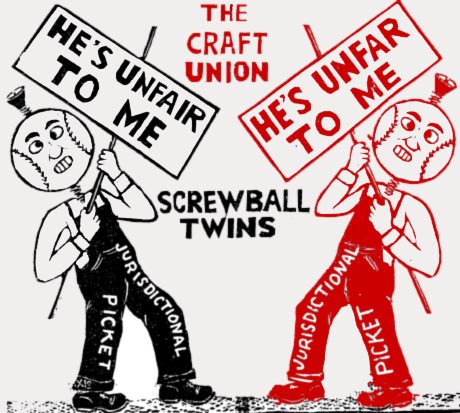

Mine workers’ leader John L. Lewis, both to defend his own union’s existence and to bring the inevitable movement for industrial unions under the control of the labor bureaucracy, split from the craft union-dominated American Federation of Labor and established the Congress of Industrial Organizations.

But the struggle to force American industry to recognize the CIO unions in auto, steel and other industries quickly assumed explosive forms that raised the specter of working class revolt. They involved sit-down strikes, in which the workers seized control of the factories and struck from inside; pitched battles with the police and strike-breakers; and deadly confrontations with national guard troops. Entire towns and cities were engulfed in class warfare for days and sometimes weeks on end. The success of these early battles was only possible because of the leading role of socialists and left-wing militants in the nascent unions.

It is absurd to even suggest that any of the highly paid, class collaborationist union leaders in either of the two camps of the divided labor movement of today would countenance such struggles. But can there be any doubt that the US financial oligarchy of today—if anything, even more besotted by immense wealth and consumed with greed than its predecessors of the 1930s—would respond to any serious challenge to its power with ferocious repression? Or that the political parties, Democratic as well as Republican, would line up behind them and support state violence against the workers?

Any doubts on this score should be settled by recalling the reaction of the government and the so-called “friends of labor” of the Democratic Party to the strike by a small union of air traffic controllers in 1981. Not only were the 19,000 PATCO strikers fired and banned from ever again working as controllers, but union leaders were arrested and dragged to jail in chains.

Andrew Stern, in a column published in the July 26 Los Angeles Times, attempted to compare his defection with the split of Lewis and the CIO from the old American Federation of Labor in the 1930s. But he hastened to follow this allusion with words calculated to reassure corporate America of his intentions, declaring: “Union members can be effective partners with employers if they start from a position of strength and equality.”

That any serious effort to organize the unorganized would entail a direct and massive struggle against the moguls of American business and the government is underscored by an insightful comment in the July 27 issue of the Financial Times. That day’s “Lex Column” notes: “Arguably the most important [reason for the weakness of the US labor movement] has been a series of legal changes. Since the late 1940s, the protections of the New Deal have gradually been eroded. By the time union-busting started in earnest in the 1980s, the hurdles would-be organizers faced had more in common with those in third world dictatorships than in much of the rest of the developed world.”

The column goes on to say that the “largely irrelevant” status of the unions in the US has helped “to boost corporate profits as a share of national income to record levels.”

Any serious struggle to organize the unorganized to fight layoffs, wage-cutting and the destruction of pension and health benefits would lead to a social confrontation of revolutionary dimensions. It would rapidly and imperiously raise the need for a political struggle by the working class against the government and both parties of American big business.

Every section of the American trade union bureaucracy is adamantly opposed to such a struggle. The so-called “insurgents” led by Stern and Hoffa, for all their hollow talk about a “new vision,” do not even speak of strikes or any other form of militant action, do not criticize the AFL-CIO’s corporatist policy of union-management “partnership,” and are totally silent on the subordination of the working class to the capitalist parties. Indeed, the Stern-Hoffa faction would not, in principle, be opposed to making a deal with the Republican Party.

The Teamsters have a record of supporting the Republican Party and Republican presidential candidates, and Stern’s SEIU, in the last election cycle, topped the list of donors to the Republican Governors Association at $575,000. Moreover, in California, the SEIU disregarded objections from the American Association of Retired Persons and liberals and lobbied against a nursing home residents’ bill of rights in order to gain bargaining rights in the industry.

Workers need to develop democratic organizations of struggle to defend themselves in their work locations and communities, and will inevitably seek to forge such organizations. But they will not and cannot arise from within the framework of the moribund and reactionary trade union apparatus.